A fortnightly newsletter by Art Kavanagh about things I’ve read

No. 15; 9 June 2021

One of my themes, in this newsletter and before it, has been the problem faced by authors who attempt to write a crime fiction series without telling the same story repeatedly, or allowing the characters, their behavioural oddities and relationships, to go stale. So, for example, I’ve written about Tana French’s first two novels, part of a series in which each story is narrated by a different member of the Dublin Murder Squad, so the author can avoid “dumping this poor character into huge life-defining crises every couple of years, in which case he’s going to end up in a hospital” (Guardian interview). I’ve suggested that Robert Galbraith’s approach to the same problem is to feature a different crime fiction trope or subgenre in each of the first three (and arguably four) novels in the Cormoran Strike series. And I’m now rereading Michael Dibdin’s Zen series, looking at how the character of his Venetian policeman remains (or doesn’t remain) consistent across 11 books.

Alan Glynn’s solution to the problem has been to write a trilogy that, in spite of the recurrence of characters from one book to another, hardly seems like a series at all. His website describes the three books, Winterland (2009), Bloodland (2011) and Graveland (2013), as his “globalisation noir” series, and “globalisation” is appropriate to the opening out and accompanying loss of specificity that we encounter between the first book and the third.

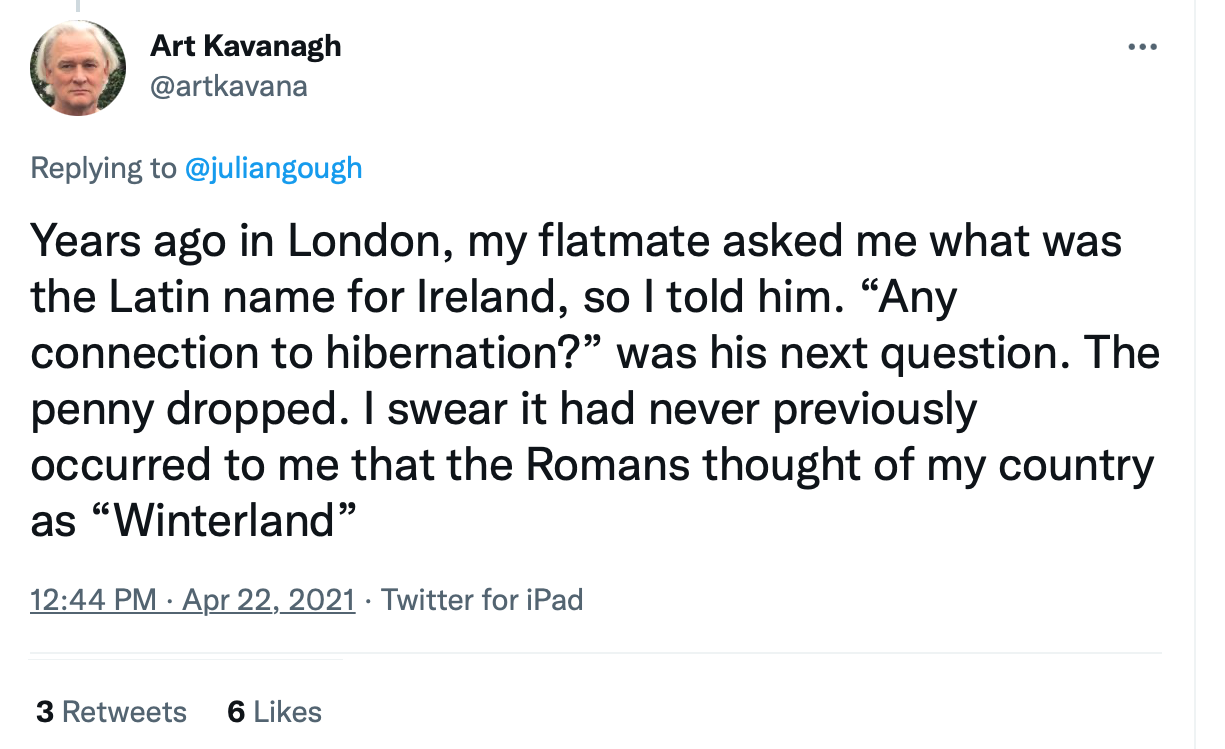

I was first attracted to Winterland by the title, for reasons which I hope are hinted at in this tweet.

The book’s “Winterland” is a property company which has been building Ireland’s tallest building, the 48-floor Richmond Plaza, down Dublin’s quays. Richmond Plaza already dominates the city’s skyline though (as it turns out) it may never be completed. Winterland Properties is in effect the personal fiefdom of Paddy Norton, a publicity-shy developer who is addicted to painkillers and self-pity, and has in his pocket a politician destined shortly to become Taoiseach, Larry Bolger. Bolger won his Dáil seat when his brother Frank, considered a maverick in the party for his environmental inclinations, died in a carcrash which also killed all but one member of the family in the other car.

When Larry begins to suspect that it might have been Frank, not the other driver, who had been drunk, Norton sets him straight:

“You have a simple choice here. You can either pursue this and keep asking questions — what happened that night, was he drunk, was he pushed, blah, blah. You can go down that road, resurrect shit from two and a half decades ago and feed it to the media on a platter.” He pauses. “Or you can go out that door over there and embrace your destiny. You can take power and run this country for five, maybe even ten years. You can change things, make a difference, fix the Health Service, build infrastructure. You can have access to Downing Street, to Brussels, you can sit on the UN Security Council, you can eat dinner at the fucking White House, whatever. But believe me, Larry …” — he holds up a finger and shakes it — “… you can’t do both.” (Winterland, p. 354)

Faced with that choice, Larry of course decides to embrace his destiny.

The plot of Winterland is fairly straightforward but Glynn presents it from several alternating viewpoints, so that the reader shares the characters’ puzzlement. As well as Norton’s and Bolger’s stories, we get episodes focusing on Mark Griffin (the solitary survivor of the crash that killed Frank Bolger, and now ironically himself dependent on the building industry, as an importer of “handmade stone and ceramic tiles from Italy”: p. 51), Dermot Flynn (an employee of the engineering firm working on Richmond Plaza, who finds himself simultaneously the target of bribery and intimidation) and, briefly, Dermot’s boss, Noel Rafferty, who is killed early in the story. The main driver of the investigation, however is Noel’s youngest sister, Gina, who can’t accept that her brother was driving while drunk, or the coincidence of his having been killed within hours of the murder of her nephew, another Noel Rafferty.

The younger Noel was the trusted lieutenant of a vicious gangster, “the Electrician”, involved in drug-dealing, trafficking sex workers and counterfeiting DVDs. It quickly turns out that a hit was ordered on Noel the engineer in the expectation that it would look like an error and that his nephew had been the real target. Unfortunately the killers also thought that young Noel was the more likely target and shot the wrong man, leaving the contractor to make hurried alternative arrangements, at the risk that the coincidence of two men with the same name dying suddenly on the same night would raise suspicions.

Winterland is set entirely in and around Dublin and has a cast of characters — drug-dealing gangsters, secretive and conspiratorial property developers and venal, self-serving politicians — that you’d expect to find in a thriller set in this city. The character who will provide the main link between the three novels is also present but he remains largely unobserved on the sidelines. He is James Vaughan, the executive chairman of Oberon Capital Group, a private investment company with global assets worth “about ten billion dollars” (p. 136). Vaughan had been JFK’s Assistant Treasury Secretary — he tells Gina that he was appointed after he discovered that Kennedy was sleeping with his first wife (p. 379). In the early 80s (i.e. under Reagan), he was Deputy Director of the CIA (p. 374). Oberon is the main investor in Richmond Plaza, and one of its subsidiaries, Amcan, is negotiating to become the tenant of a large chunk of the development (and change the name to “the Amcan Building”).

Vaughan is even less happy about publicity than Paddy Norton is, and quietly departs to catch a flight back to New York leaving the latter to deal with damaging revelations about Richmond Plaza.

The next book, Bloodland, is partly set in Dublin but the canvas is expanded to take in a repurposed copper mine in the Democratic Republic of Congo, a fatal helicopter crash off the coast of Donegal, an Italian citizen working for the UN and the ignominious collapse of a campaign for the US presidency. Gina, the central character in the first book, does not appear in this one, which instead centres on an out-of-work journalist, Jimmy Gilroy, who has been paid an advance by a publisher to write a biography of one of the victims of the helicopter crash. She was Susie Monaghan, an exotic (and reputedly coke-addicted) model and soap star who lived fast, died young and burned out spectacularly. As Gilroy discovers that the real story isn’t about Susie after all, he worries that he’ll have to return the advance, which is now partly spent, if he abandons her biography.

He’s not the only one who is regretting having accepted an advance. Former Taoiseach Larry Bolger is not coping well with the loss of office. The incentives held out by Paddy Norton haven’t come to fruition. Instead of 5 years in office (or maybe even 10) he lasted only 3, and he’s now feeling like the forgotten man. On top of that, he’s not satisfied that he’s being shown the respect due to a sometime leader of the country. He’s supposed to be working on his memoirs but he has no idea where to start. When he hears that a journalist is digging into the death of Susie Monaghan, he regrets having dropped in to a conference on corporate ethics a few years earlier, during his time in office.

James Vaughan was present at that conference, as were his protégé, Clark Rundle, and Dave Conway, whose company owned the exhausted copper mine in Congo. Conway’s subsequent reputation as a sharp businessman rested on his having made a killing in selling the ostensibly valueless mine to Rundle’s company. Ironically, Conway wasn’t interested in the mining company which he’d inherited and, like any self-respecting Irishman aspiring to unimaginable wealth, really wanted to be a property developer. So he used the money from the mine deal as the basis on which to borrow hundreds of millions of euro to build an insanely ambitious development named Tara Meadows, and eventually ended up facing bankruptcy.

In the end, Jimmy Gilroy went to New York, where he met Ellen Dorsey, an investigative journalist working for a monthly print magazine, and together they brought to an end the presidential ambitions of Clark Rundle’s brother, Senator John Rundle. The fallout also exposes what Clark Rundle’s company wanted with the former copper mine: it also contained deposits of an extremely rare mineral used in robotics. James Vaughan comes out of the whole thing in better shape than his former protégé:

But as far as Vaughan himself is concerned, the damage is significant. There’s no question about that. At least it’s contained, though, it’s private. (Bloodland, p. 410)

He can no longer secretly extract the mineral from the Congo, but he knows of another source, in Afghanistan.

The trouble with mining in Afghanistan, however, has always been the country’s woefully inadequate transportation infrastructure.

But it seems as if that might be about to change.

The Chinese had embarked on a long-term project to establish a new trans-Eurasian corridor, a sort of modernised version of the old Silk Road. Vaughan’s idea is to get in early, establish a foothold in Logar. Fly under the radar for a while and see what happens. (p. 411)

China was his rival in bidding for mining licences in Congo. In Afghanistan, its Belt and Road Initiative might be his lifeline. Things change.

Although the final book in the trilogy is set mainly in New York (where Vaughan is based), he and his companies seem to be peripheral to the action for much of the story’s length. Paloma Electronics has been the employer of Frank Bishop, an architect who was let go because of the recession in building and, in his 40s, got a job managing an electronics retail branch in a run-down, failing mall. He loses even that job, for which he’s obviously unsuited. Then his 19-year-old daughter is shot dead by a SWAT team when her college boyfriend takes part in the assassination of the CEOs of an investment bank and a hedge fund, and the attempted assassination of the CEO of a private equity firm.

Lizzie Bishop hadn’t known what her boyfriend was up to and hadn’t been involved in planning the killings, but she steps up when he and his brother are too exhausted, shocked or stoned to negotiate with the FBI conducting a siege of their apartment. This leads the authorities and the media to suspect that she might have been the leader all along.

In the meantime, Jimmy Vaughan, now 82, has decided to retire. His successor will be Craig Howley, the former Pentagon official who helped him to set up his Afghan operation. But Howley has a very different approach to publicity than Vaughan’s, and so attracts the attention of Frank Bishop. Frank feels that his daughter’s work has been left uncompleted, in that the original private equity target survived. So, Frank decides that Howley is an appropriate substitute, particularly as he is ultimately the boss of Paloma.

With Craig Howley dead, Vaughan is unable to resist resuming control, however briefly, of his financial empire. He finds that some publicity — some exposure — can’t be avoided, any more than age or death can be.

Originally posted on Substack (Talk about books), 09–Jun-2021.